Available in Español

By Marsha Davis

During our “pause for the cause,” AMKRF has entered a time of organizational reflection and analysis building. As a part of our work, we are sharing reflections about what we’ve learned in the process of building relationships with one another and analyzing power, white supremacy, oppression, alongside liberation.

Marsha Davis

“If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair.” – Shirley Chisolm

I’ve learned many lessons from my family of Haitian immigrants. My parents came to this country seeking better opportunities for themselves and their children; and as I was growing up, they drilled into my head the importance of taking “my seat at the table.” While they believed in America’s potential, they weren’t naive about America’s reality. They knew that my status as a black woman in a white-led country left me vulnerable to all sorts of discrimination. My parents knew that in order to take advantage of all that America had to offer and to have the most self-determination over my own life, I had to be in the rooms where the decisions were made.

So I worked hard and navigated white supremacy and patriarchy like Neo from The Matrix. I had a singular mission: get a seat at the table. I made career choices that matched my ambition. I graduated from Harvard and set out to change the world. What my parents never told me, however, was what to do once I got my seat at the table. Like generations of parents from the African diaspora, they put all of their energy into pushing their children towards more opportunity, without an idea of what the landscape would look like when we got there.

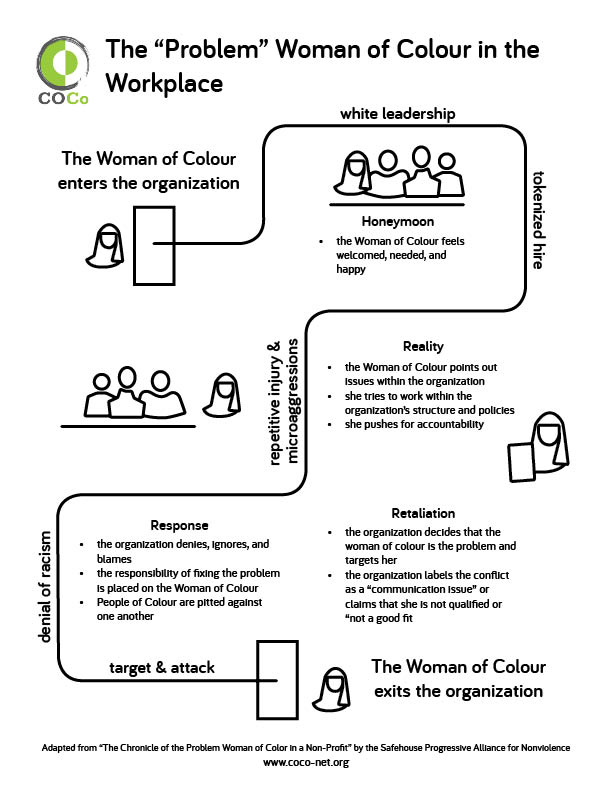

My journey into leadership mirrors the journey of “The ‘Problem’ Woman of Color in the Workplace” depicted by the Center for Community Organizations (COCo).

I faced challenges that my education and family didn’t prepare me for. Like, what to do when your white boss asks you to convince another black employee that the organization doesn’t have a race problem. Or when institutional racism is so entrenched you can guess which employees work in administration by looking at the color of their skin. Or how to address legitimate concerns about how people of color (POC) are treated by your organization while finding the time to do the job you were actually hired to do.

Now that I have a seat at a philanthropic table, influencing how funds are redistributed, I’ve looked to my black queer feminist ancestors for guidance on how to lean into this moment. I find myself returning to Audre Lorde’s words, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”

I look to the work of social justice movement builders, and all of American history, to remind me that while I’ve been able to reap benefits from the systems of this country, the system is still rigged. Philanthropy sits at a complex point in our capitalist system, where it is both a tool of support for marginalized communities while also being funded from a system that allows the top 1% to horde wealth to the detriment of the remaining 99%.

As a first-generation American who has, in some ways, lived into the American dream, I am deeply personally invested in helping this country to embody the values it says that it espouses–values of human dignity, self-determination and an engaged democracy where everyone is empowered in their pursuit of happiness. Many of the “best practices” of philanthropy actually move funders further away from those values. For example, many funders have strict restrictions on what grantees can use grant dollars on, leaving nonprofit staff in the position of ignoring what is best for their organization and community so they can contort to fit the funders’ requirements. These practices enhance the control of the wealthiest and uphold the values of “the master’s house.”

I’m not interested in reproducing those systems at the Mandel Rodis Fund. With our team, I am grappling with the concept of “genuine change.” Is it possible to create a reparative relationship between funders and grantees where we are co-conspirators in the fight for liberation? Can we work together to dismantle the master’s house with the understanding that inequitable systems hurt us all, both the wealthy and the poor? Can we build alternative systems that strengthen and empower our entire community? I owe it to my ancestors, my immigrant family, and my current community of social justice warriors to do the work to answer these questions.