Available in Español

One of the great joys of my life is hearing the stories of people I admire and appreciate. So many friends, grantees, staff, consultants, and leaders in movement work have trusted me with their stories. Often, there is an inherent power dynamic in these relationships, and vulnerably sharing reflects a leap of trust. In hearing others describe what led them to do what they do, I have come to see the importance of telling my story and sharing publicly why I do what I do. My hope is that sharing the paradoxes and questions I sit with is a step towards the transparency and accountability which are so essential for building trust and community.

Embracing Contradictions

Every day I wrestle with paradox both personally and in my work as the Chief Visionary Officer of the Amy Mandel and Katina Rodis Fund (AMKRF).

As a 67-year-old Jewish, lesbian, who lives with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), a fatiguing, relapsing, and remitting illness, I have experienced anti-Semitism, homophobia, and ableism first hand. And as a wealthy, white funder, I carry class and racial privilege. Given the circumstances of my birth, I have had access to all of the medical, educational, financial, and other privileges that are available to those of us with wealth and white skin.

AMKRF and the Tzedek Social Justice Fellowship are working towards a world in which everyone thrives. At the same time, the resources that support AMKRF are a product of generational class privilege and wealth. These resources were accumulated within a capitalist and white supremacist system, and these systems build upon and maintain vast inequity.

I often find myself trying to decipher “the best” way to work, which can lead to immobilization and inaction. And, I continue acting–utilizing my resources philanthropically–knowing that the decisions I make are imperfect.

These facts, while seemingly contradictory, are equally true.

With the help of trusted colleagues, I continue to be challenged to wrestle with these paradoxes. I believe that one step in disrupting unequal power and systemic oppression is by naming the tensions at the center of our lives.

Evolution of a Social Consciousness

Amy Mandel

I was born in Cleveland, Ohio in 1952. My first exposure to social justice activism came in the fifth grade when I began to read about the resistance to the Nazi Holocaust. As a Jewish person, this had an extraordinary impact on me. In 1962, this Holocaust was very recent history. I grew up asking myself will a Holocaust happen again, and will it happen to me? In many ways these questions have never gone away, and I feel the lingering fear as I watch the rise of fascism.

But learning about Holocaust resistance lessened the fear and hopelessness I felt. What I learned is that bridges are essential for survival. What the experience of my ancestors tells me is that without bridges and strong connections with allies, we are isolated and open to attack and even death. This learning has become central to my work as I’ve sought partnerships with organizations, leaders, and activists who are invested in building relationships and working across differences.

In the summer of my 2nd grade year, I developed Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis. I experienced so much pain and swelling that I had difficulty walking. My doctors suspected a warmer climate and daily swimming would enable my recovery, so my family relocated to Palm Beach, FL. This willingness to relocate for my health’s sake remains one of the biggest gifts my parents ever gave me. It proved to be a real sacrifice for my mother and father. Dad’s business was based in Cleveland, Ohio, and because we did not have the tools for remote work that we have today, he spent two thirds of each month away from our family.

In Florida, I was one of approximately ten Jews in a school of about 600 kids, and because we were Jewish, we were treated with some suspicion and excluded from social clubs, church activities, and dance classes.

During my years in Florida, my father was deeply entrenched in building the business that eventually became a source of extraordinary family wealth. I did not understand at the time how much this wealth would come to define my life.

In 1965, we moved back to a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio. There, I became engaged in social change for the first time. At first, I was involved in charitable works like raising money for children experiencing famine in Biafra (Eastern Nigeria). But by eleventh and twelfth grade, I was volunteering for the campaign to elect Eugene McCarthy, a member of the Democratic-Farmer-Labor party, and increasingly compelled by events organized by the Students for a Democratic Society.

My first experience with direct action also brought my first direct experience with homophobia. In resistance to the rule at my public high school that girls wear skirts, a few female students and I chose a day to protest by wearing pants. One of my teachers let me know exactly what he thought, “Miss Mandel, I will not have you coming into my class looking like a dyke.” Although our actions led to loosening of the dress code, we still had to keep skirts in our lockers to change into for the classes led by teachers who objected.

In 1969, I moved to Waltham, Massachusetts to attend Brandeis University. I lived in the Boston area for the next 32 years. Throughout college, I became increasingly politicized, participating in anti-Vietnam War protests, learning about feminism through circles of women (several of whom came to be part of the Weather Underground), and joining the swelling post-Stonewall LGBT movement. I also explored communal-collective living by pooling resources for food and rent, sharing household responsibilities, and making collective decisions at weekly house meetings.

The Kent State shootings and waves of civil disobedience in response to virulent racism provided a backdrop that activated me. I got a job at the National Student Strike Center. Our goal was to shut down universities via sit ins in response to a range of injustices. I had a burgeoning consciousness about the whiteness of student movements.This awareness has only grown over time.

After college, I found continued community in communal living and as a part of the Red Basement Singers. We had the privilege of performing at events benefiting social justice focused organizations. But we also used the power of song to sustain collective action by singing at demonstrations and political rallies. By the late seventies, I was a member of a Marxist-Leninist organization dedicated to working within unions at hospitals and factories in the Boston area. Even then, I was troubled by how much our work was driven by a deep assumption that “we” knew what workers needed. Our analysis was extraordinarily limited, and our whiteness and the middle-class status of most organizers was reflected in so much of what we did.

Throughout my activist life, I was self-conscious about my wealth. I felt startlingly alone. And yet I felt a deep need to belong. Activism and organizing were medicine for me. I felt a need for connection, a need to build community. I found that in social justice work.

But I also noticed the failures of social movements and became increasingly uncomfortable with what seemed to me to be the arrogance of many organizers. I began searching for something else. I took a computer class and learned that I loved software engineering. After years of working in social justice, it was a relief to do work with clear right and wrong answers. I worked in this field for several years, but my justice consciousness found me there as well. The company I worked for provided software solutions for newspaper companies. One of our clients was the New York Post which was owned by Rupert Murdoch. In the mid-80s in the United Kingdom, there were a series of technology-related layoffs at Murdoch-owned newspapers that resulted in a labor strike. When I was asked to go on site to debug software, I refused because I was not willing to cross the picket line.

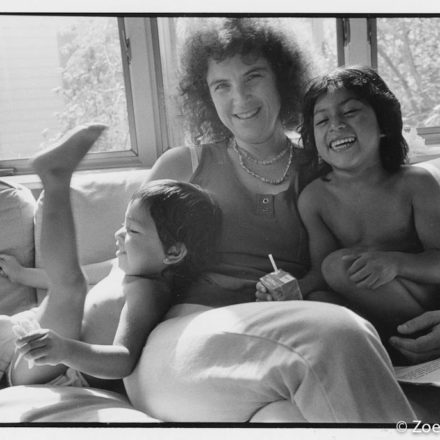

In the late 80s I adopted my daughters: Alicia in 1987 and Daniela in 1988. For several years, I dove into mothering, a luxury afforded by economic privilege. My hope for a better world was channeled into parenting my daughters and into classes I taught to other moms, that focused on using the expertise we all have to ignite change – in ourselves and in our communities.

In the late 80s I adopted my daughters: Alicia in 1987 and Daniela in 1988. For several years, I dove into mothering, a luxury afforded by economic privilege. My hope for a better world was channeled into parenting my daughters and into classes I taught to other moms, that focused on using the expertise we all have to ignite change – in ourselves and in our communities.

Instead of juggling work and parenthood, for the first time I relied exclusively on my trust fund to support our family. My parents had established trusts for their children when my Dad’s company, Premier Industrial Corporation, began selling stocks to the public in the 1960s. Their initial investment included $20,000 of stock, intended to fund our college educations. In 1964, the company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange and the amount in each trust increased greatly as the company grew.

In the fall of 1991, I met my wife, Katina Rodis, and we began a commuting relationship. After five years Katina moved to the Boston area to live with my daughters and me. We lived and parented together for many years before our marriage was recognized legally. In 2008, wanting to stand up and be counted as a queer couple and even though same-sex marriage was not yet legal in NC, we got officially married in the state of Massachusetts.

The year I turned 40, I became incredibly sick with a debilitating illness, which was eventually diagnosed as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). Katina came into our relationship with her own lived experience of chronic and unrelenting illness, and I was fortunate to have someone close from whom I could learn the territory. Disability dramatically changed my life and our children’s lives. The experience of moving from health to unwellness has been a significant one, and I am still making sense of how it informs my life and work.

In 2002 we moved to Charlotte, North Carolina, in order for me to receive twice-weekly infusions of the experimental drug, Ampligen. My doctor was a specialist in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Fibromyalgia and one of only a few doctors in the country with permission to do an Ampligen trial. In 2003, we relocated to Asheville. Although I have experienced several major relapses over the years, my health has improved gradually and significantly. This is another paradox that characterizes my life. Despite all my self-care practices and my deep commitment to healing, my health is vulnerable. I am never certain how I will be able to show up for the work. Yet every day of wellness feels like nothing short of a miracle which allows me to act on my desire to harness my wealth for systemic change.

It’s this personal journey that I bring to my work.

Read part two here and part three here.