Available in Español

37 Montford Avenue, AMKRF/Tzedek Office

In November 2016, AMKRF and the Tzedek Fellowship established a physical office for the first time at 37 Montford Avenue. Currently, Asheville is one of the most rapidly gentrifying cities in the country, and the capacity to own property or secure a lease is an extraordinary privilege in a place where space is increasingly inaccessible.

In Asheville, stories of place and space routinely erase Cherokee presence in this region and the ongoing consequences of redlining, urban renewal, and other forms of systematic racism on Black and Brown communities in Asheville. Instead of ignoring these histories, we wanted to know more about the place that is our organizational home and to share the story with others who gather there. We also found ourselves asking how can this space support more than our organization’s mission. As a result of that question, we developed a practice of opening our space to others engaged in working towards social justice in Asheville. 37 Montford Avenues is the home office of AMKRF/Tzedek, but it also supports the work of local grassroots organizations, opportunities for healing, storytelling circles, strategic planning sessions, circles for learning and reflection, and more.

What follows is not a complete history, but we share it to ground ourselves in the realities of this place and to inform how we utilize our resources.

Before North Carolina and before Asheville, the convergence of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers was a center of life for Cherokee people. Since at least 8,000 B.C., people were residing, celebrating, and tending the lands alongside the river waters. Ancient Cherokee sites abound on what is currently downtown Asheville and the Biltmore Estate.

An established Cherokee trading route ran alongside Reed Creek, the corridor we know as Lexington Avenue and Broadway. Cherokee people were laid to rest in graves where a tiny Patton Avenue park now sits across from what is currently the Kress Building. Lands reserved by the Cherokee for feasting and ceremony are the same pasture lands adjacent to the Biltmore Estate ticket office.

The colonization of western North Carolina and the theft of Cherokee lands happened over a period of two hundred years. In 1540, Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto trekked through Western North Carolina in search of gold and a path to China. Following the American Revolution, the State of North Carolina bestowed a land grant to Colonel Samuel Davidson who settled the Blue Ridge Mountains, the same land that was home to Cherokee communities. By 1790 the United States Census counted 1,000 residents in the area. In a deliberate effort at erasure, these counts excluded Cherokee peoples.

Despite the fact that these lands already had Cherokee names (Suwa’li-nunnohi and Untokiasdiyi, for example), Buncombe County was officially organized on April 16, 1792. In 1797, the county seat, Morristown, was incorporated and renamed “Asheville” after North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe. The ties of the Cherokee to this land were systematically destroyed through the official process of boundary drawing and mapping.

The process of colonization culminated in the forcible removal of vibrant indigenous communities in late spring 1838. Through the events known as the Trail of Tears, U.S. troops evicted indigenous people from their homes, imprisoned Cherokee people in removal camps, and force-marched 16,000 Cherokee for 800 miles. At least, 4,000 Cherokee died in the process.

“We, the great mass of the people think only of the love we have to our land for…we do love the land where we were brought up. We will never let our hold to this land go…to let it go it will be like throwing away…[our] mother that gave…[us] birth.”

Cherokee Legislative Council, New Echota July 1830

Image used with permission from Crossroads Summer and Fall 2010, a publication of the NC Humanities Council

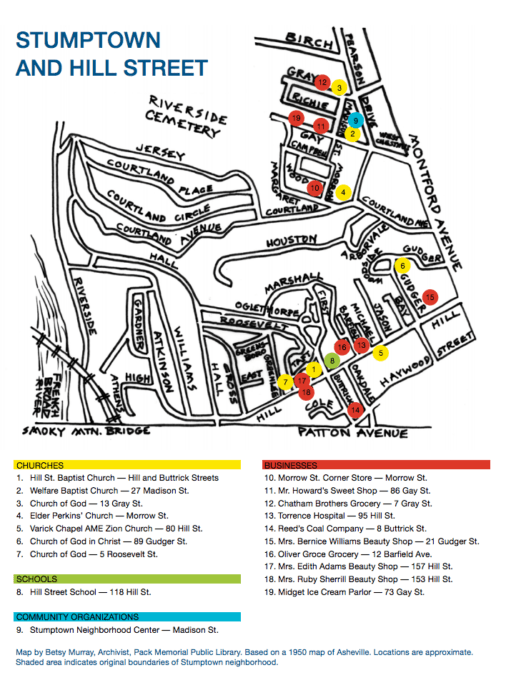

Less than fifty years later, a thirty-acre tract designated Stumptown was established as a Black neighborhood within Montford. Stumptown became home to families who worked in Riverside Cemetery, at the Battery Park Hotel, and for wealthy whites throughout Montford. By the 1920s, Stumptown’s population exceeded two hundred families.

Beginning in the 1950s, urban renewal (a misnamed effort that purported to enhance cities but in effect destroyed communities of color) focused on Asheville’s Black neighborhoods–East End, Burton Street, Southside, and Stumptown. Residents were evicted. Homes were bulldozed. By the early 1970s, Stumptown was largely destroyed. Evidence of Stumptown is barely discernible on the land where the Montford Community Center now sits. Montford remained intact as a neighborhood for Asheville’s upwardly mobile white professionals.

By 1977, Montford was entered on the National Register of Historic Places. While celebrated as one of the U.S.’s most beautiful historic neighborhoods and as an architectural dreamland, the history of indigenous people and Black communities in Montford is largely erased.

The building where we work is established on colonized land. Colonialism and oppression rely on erasing communities’ histories. As settlers working toward social justice, we want to challenge a simple story about Montford as a historic avenue and center of white prosperity in western North Carolina. We are not entitled to this property and yet as leaseholders on it, we want to call into question that this place “belongs” to us. In the service of community and accountability, we share our office space with other groups engaged in social justice work at no charge.

Sources:

- Cherokee Reclaim Landmarks of Ancient Asheville (Asheville Citizen Times, 2015)

- Cherokee Heritage Trails

- Stumptown: A Dramatic Disruption (Crossroads, 2010)

- Discovering Stumptown (Montford Newsletter, 2011)

- A Visit to the Old Village of Stumptown (Montford Newsletter, 2011)

- A Stumptown Postscript (Montford Newsletter, 2011)

- The History of Asheville (Thomas Wolfe Memorial)

Local Learning Opportunities:

Resources on Decolonization and Settler Accountability: